Itâs easy to remove a sentence of unwanted audio in post-production. But, what if you need to add dialogue or narration after all the talent has gone home when production concludes? Not so easy.

You could try to get the talent back, return to the identical location and use the same mic and equipment. But, what if that is not possible?

In this article weâll explore the tricks filmmakers use to make two pieces of audio recorded in different places, possibly with different mics, sound like they were captured at the same time. To understand the scope of the challenge we need a quick physics lesson.

The Science of Sound

Sound travels at 1,100 feet per second. That may sound fast, but itâs downright lethargic when compared to the blazing speed of light at 983,000,000 feet per second. We know this from our own experiences with fireworks and lightning â we see the flash of light before hearing the sound.

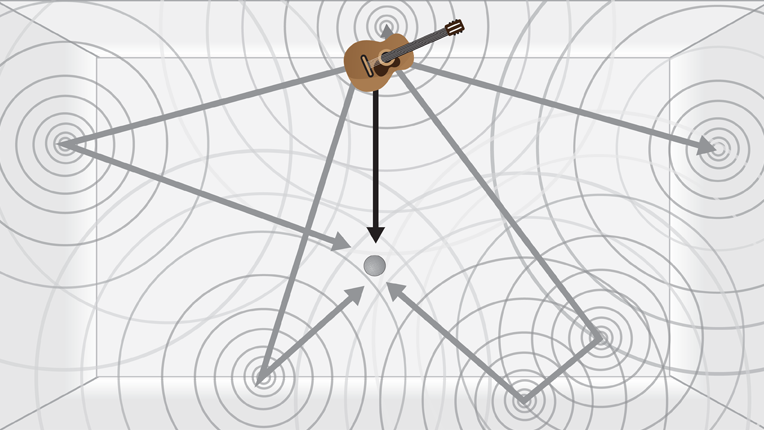

The sluggishness of sound travel causes filmmakers countless headaches. Slow speed is the cause of that cavernous sound when the mic is too far from the sound source. Like attempting to record a college lecture from the last row in the classroom â especially when the professor is writing on the whiteboard with her back to the class.

In this example, the professorâs voice bounces around the room â each reflection arrives at the microphone at slightly different times creating a chaotic cacophony of sounds. This phenomenon, called reverberation, can give an audience helpful clues to determine the size and acoustic characteristics of the recording location. Want to make a politician sound like they are addressing a huge arena, even though they are in a recording studio? Add reverb.

Room Personality

Each room has its own unique acoustic personality. The challenge here is to get two pieces of audio captured in different rooms to sound the same. Letâs look at the factors that contribute to the roomâs character.

Hard surfaces generally reflect sound and include tiled floors, glass, painted walls and hard plastic chairs. Soft surfaces absorb sound and include carpets, draperies, upholstered furniture and even people. Lots of hard surfaces make for a vibrant, or âliveâ room; soft surfaces make for a quiet, or âdeadâ room.

There are situations when filmmakers may need to add ânatural soundâ (also known as background or ambient sound) to a piece of audio captured in a studio. For example, in order to have an authentic grocery store experience we need the natural sounds of beeping scanners, squeaky shopping carts, a murmur of conversations and the mundane music played over the storeâs sound system. You could try to recreate these sounds with sound effects, or you could go back to the store and just record the storeâs natural sounds.

Itâs possible you recorded enough natural sound when you were on location. Review your recordings and listen for portions where there is only background sound, without dialogue. You can sometimes loop a small clip of background sound to make it last longer. Pros make a habit of recording background sound at each shooting location so they can add it to the mix later if needed.

Pros make a habit of recording background sound at each shooting location so they can add it to the mix later if needed.

Just like rooms, mics have personalities too. An expensive ribbon mic might enhance the deep resonance in a male announcerâs voice, whereas a condenser mic might make the same announcer sound bright and crisp. How could you match this? An equalizer (EQ) can help match the sound by altering the tonal characteristics of the audio signal. Weâll learn how to do that next.

High Tech Solutions

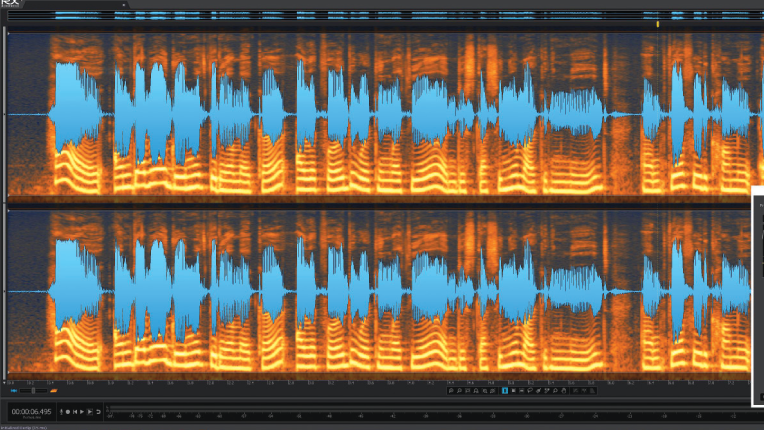

iZotopeâs RX 4 ($299) and pricier RX 4 Advanced ($999) offer a suite of plug-ins that add functionality to your existing audio production software. Itâs compatible with Logic, Pro Tools, Audition, Cubase, Vegas, Sound Forge and more. These plug-ins also work with video editing software, including Final Cut Pro and Premiere.

The standard RX 4 package includes tools for hum removal; rebuilding of distorted audio caused by overload (clip); removing clicks and pops; a spectral analysis tool that mends unusable audio by filling in missing gaps; and noise removal. The step-up RX 4 Advance adds tools to remove reverberation, EQ match, ambience match and more.

Adobe Audition software has a â match volumeâ feature that makes quick work out of setting a standard volume level for a variety of different clips. Appleâs Logic Pro âmatch EQâ plug-in offers filmmakers a method to match the EQ characteristics of various audio recordings. These types of tools â which are available from a variety of vendors â can get rather technical. Donât be shy â just give them a try. Most have helpful presets to get you started. Remember, the undo command is your friend.

Challenging Scenarios

Letâs use three scenarios to explore sound matching challenges and solutions.

Scenario #1. Michael is editing his documentary about the health effects of a deadly African virus. Recently he learned of a new procedure that lessens the chances of infection. Michael could not have foreseen this breakthrough when he wrote the script â the narrator mentioned nothing about it. The new content must be added or the documentary will be outdated before it is finished. The narrator lives 1,500 miles away and the final edit is due in two weeks. Yikes.

A solution would be for the narrator to record the new segment and send the file to Michael. Letâs assume the narrator was originally recorded outdoors in a field. The new recording needs to have the same natural sound â hopefully you have some available from the original shoot.

Itâs easiest to record the narrator in a dead room, then add the ambient location sound from the field. If the narrator cannot use the same mic, then Michael can use a âmatch EQâ tool to minimize mic personality â or just experiment with a standard equalizer.

Scenario #2. Emily is in the process of editing a family history video when she discovers her 88 year-old grandmother got an important fact wrong during an interview. Emily recorded the interview in a living room where the acoustics were warm and soothing. Unfortunately, her grandmother is now in a care facility and the only way to re-record the audio is in her hospital-like room that has the shrill acoustics of a bathroom.

Room acoustics are the biggest challenge here. The first thing for Emily to do at the care facility is get the mic close â I mean really close â to grandmaâs mouth. Getting the mic close maximizes the loudness of grandmaâs voice, thereby minimizing the ability of quieter reflected sounds to creep into the recording. Also, close the draperies â most any window covering will absorb sound better than the glass it covers.

If at all possible, Emily should use the same mic as in the original recording. Once re-recorded, Emily could use a âmatch volumeâ tool to set the levels the same â or just manually experiment to match the levels. If her budget allows, the RX 4 Advanced âambience matchâ tool could do wonders in this situation.

Scenario #3. Meet Sam, a video editor with a small production company. Her task is to take dialogue recorded from around the world and edit it together so that it sounds like a group conversation taking place over a speakerphone. Different mics and locations were used for each recording â everything from a studio to a kitchen table.

The good news here is that expectations are already low for the quality of sound emanating from a speakerphone. Sam will actually have to reduce the quality of dialogue captured in a studio. Sheâll use the âmatch EQâ tool to simulate the typical speakerphone sound through reducing the tonal quality of the clips.

Fixing sound matching problems in post-production is workable, but itâs far from fail-safe. The best strategy is to avoid having to match sounds in the first place. Do this by making every effort to use the same mic and room for each recording session. But if that is impossible, there are tools to help you trick your audience.

SIDEBAR: Sounding it Out

One way to assess a roomâs acoustics is to clap your hands. In a professional recording studio you only hear the sound emanating from your hands â all other surfaces are designed to absorb and minimize reflections. Try the same thing in a typical garage and youâll experience the sound as it bounces around the hard surfaces.

David G. Welton is a professor of Media Studies.